Vertigo, Ice, and Celluloid: Robert Redford’s Andean Odyssey | Ski in Portillo.

The incredible true story of Robert Redford filming "Downhill Racer" in Portillo, Chile. Discover the "Andean Curse," the 35mm cameras, and the struggle against the winter of 1969. Ski in Portillo.

PORTILLO

Mauro

1/5/20264 min read

The silence at the Laguna del Inca is no ordinary silence; it is a physical presence that presses against your eardrums, heavy with centuries of legends and the frozen whisper of glaciers. But in the winter of 1969, that silence was profaned by a sound foreign to the high Andes: the mechanical whir of 35mm Arriflex cameras and shouts of "Action!" defying the white wind.

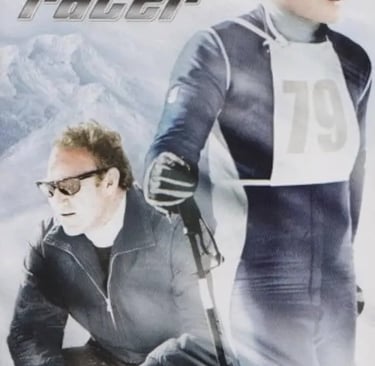

Robert Redford, Hollywood’s golden boy, hadn’t come to Portillo for the afternoon sun on the hotel terrace. He had come to wage a battle against gravity, against the film industry, and ultimately, against the mountain range itself.

This is the story of Downhill Racer, a production born from a blind ambition for realism that nearly ended up buried under the avalanches of one of the world's most implacable mountains. For the modern skier, sliding on carbon fiber boards over satellite-groomed corduroy, what happened that year in Portillo sounds like a fiction more incredible than the movie itself.

The Vision: Truth at 80 Miles Per Hour

By the late 1960s, Robert Redford was fed up. He was tired of Hollywood’s green screens, of actors faking speed in front of fans in a Burbank studio, and of sports movies that lacked soul. He was a real skier—a man who understood that downhill racing isn't a dance; it’s a duel with fear.

As the producer and star of Downhill Racer, Redford set out on a mission his agents thought was madness: to film skiing as it had never been done before. He wanted the audience to feel the burn in their quads, the biting wind on their faces, and the sheer terror of losing an edge on a sheet of blue ice.

To achieve this, he needed snow in August. He needed slopes that would make even the best World Cup racers think twice. His map led him to a remote corner of Chile, to a bright yellow hotel embedded nearly 3,000 meters high: Portillo.

Redford didn't arrive alone. Beside him were a young, hungry Gene Hackman and a technical crew—most of whom had never set foot on a real mountain, let alone one that didn't speak their language and seemed to possess a dark, sovereign will.

The Siege: The Yellow Fortress Under the "Blanco Total"

When the production crew landed in Santiago and climbed the "caracoles"—the 29 hair-raising switchbacks leading to the border—the culture shock was immediate. Portillo in 1969 was an isolated ecosystem, a fortress of civilization surrounded by 5,000-meter peaks.

Logistics that we would solve today with a drone and a few clicks were, back then, a nightmare of biblical proportions. The 35mm cameras were metal monsters weighing nearly fifty pounds. Moving these machines across the slopes of Juncalillo or Roca Jack required superhuman physical effort. There were no GoPros. To capture the famous first-person point-of-view shots, expert skiers were recruited to ski with these heavy metal boxes on their shoulders, balancing the weight while descending at speeds bordering on disaster.

But the mountain had other plans. The Andes decided to welcome Hollywood with one of the most violent winters in living memory.

The Calvary: Time Stands Still at the Lake

Soon, the shoot became a siege. Massive storms—what locals call the "blanco total" (total whiteout)—unleashed themselves upon the hotel. For weeks, the production was trapped. The outside world ceased to exist. Supplies grew thin, and the budget bled out with every hour of inactivity.

Imagine the scene: the interior of Hotel Portillo, saturated with cigarette smoke and the smell of hot wax and paraffin. In one corner, an obsessed Robert Redford, obsessively reviewing the script as his face lost its Los Angeles glow to the pallor of confinement. In another, Gene Hackman, whose acting intensity was fueled by the claustrophobic atmosphere. The tensions on set weren't acted; they were the result of weeks of forced isolation.

The storms were so fierce that the roar of the wind against the windows made sleep impossible. The outdoor rigs they had painstakingly built were literally erased by the snow. The exhausted crew began to whisper about "The Curse of the Andes." The realism Redford sought was being delivered, but in a form much more brutal than he had ever imagined.

The Miracle of the Descent: Ice Becomes Art

When the skies finally parted and the Andean sun—implacable and blinding—bounced off the slopes, the crew emerged like soldiers from a trench. They knew they had little time before the next storm hit.

Defying the slopes we categorize today as "Expert" or "Extreme," Redford and his camera-skiers hurled themselves into the abyss. Those shots in Downhill Racer, where the horizon oscillates violently and the sound of edges against ice sounds like the scream of a wild animal, were achieved by cheating death. Every take was a gamble. If the cameraman fell, he didn't just lose his life; he destroyed an irreplaceable camera thousands of miles from civilization.

Redford’s obsession with authenticity paid off. He filmed racing in a way that, even today in the era of 4K and digital stabilizers, feels fresh and terrifying. He captured the solitude of the racer—that moment in the starting gate where the world disappears and only the next turn remains.

The Legacy: The Mountain That Couldn't Be Tamed

Though the shoot was a "calvary," the result was a cult masterpiece. Downhill Racer is not a happy movie. It is cold, hard, and competitive—just like the mountain. When it premiered in 1969, audiences were stunned. They had never seen skiing like that. The "documentary style" of photography, born out of necessity and Portillo's rugged terrain, forever changed the way action sports are filmed.

For those of us addicted to the snow, this story is a reminder of the essence of our passion. Portillo isn't just a luxury destination; it is a sanctuary where Hollywood tried to measure its strength against nature and barely made it out alive. Every time we descend those Chilean slopes, we are crossing the same lines Redford carved with his wood-and-metal skis, under the impassive gaze of the Laguna del Inca.

Today, Redford's story is part of the hotel’s soul. Legend has it that sometimes, when the wind blows just right through the crags, you can still hear the echo of a 35mm camera spinning, searching for the perfect descent in the vastness of the Andes.